Yesterday afternoon, I gave a workshop at my daughter’s high school about the writing process. It’s a speech, in one way or the other, I’ve given many times in many venues. I try to be entertaining and informative, but at the end of the day, I’m skirting the surface of what it is to be an author. In other words, I rarely investigate and chronicle my own workcraft.

Recently, I’ve launched into my next book project THE WICKED AND THE GOOD (loving this title!). After this most recent talk, I was inspired to use this newsletter to turn the lens on my craft, to give readers an inside look from start to finish on what it is to research and write an 85,000-word narrative history.

As the above subtitle promises, I will be offering examples from my own work, especially from this most recent project. I hope you follow along with me on this journey, all the way from the genesis of the idea, to the research, to the structuring of the book, to the writing and revision process, and through to the publication (what is that first bookstore appearance like…or that first good/bad review?!?!).

Let’s begin almost at the beginning: the book proposal. It’s an art in and of itself. One has to both sell the idea and oneself with the proposal—and do so in a concise, entertaining, pitchy way. My agent, Eric Lupfer, and I probably worked on half a dozen revisions before we got it right. Fortunately, Matt Harper, who aptly is an editor at HarperCollins, liked the proposal, and it’ll be on bookshelves and digital readers in Spring 2025. That makes me 10 out of 11 on such proposals. That one miss still stings!

Below is the opening letter for the proposal, and then the first couple of pages. As I’ll be doing throughout this journey, I’ll give a deeper dive for paid subscribers, who, in this case, will get to read the full 14-page pitch.

A caveat on proposals. They are sales documents, not finished works of literature. No doubt my view on this narrative—and the individuals who lived it—will shift as my knowledge and insight deepens. In other words, don’t hold me to it!

Hope you share with any and all of your writer friends! Away we go…

Dear Matt,

A young undercover detective, CEO of the world’s biggest company, labor crusader, and a secret Irish crime organization—all these come together in a war at the dawn of the Gilded Age that captivated the nation and shaped the very soul of America. This is the short pitch for my new narrative history, THE WICKED AND THE GOOD.

Four years have passed since my last book FASTER published during the first outbreak of COVID. During that time, I have been searching for a story that excites me to my core. A few have intrigued me, but nothing compared to this stunning true-crime story about the infamous Molly Maguires, and I am already well on the path to cracking it.

As you know, I've written on various subjects, from skyscraper wars, to four-minute miles, to Russian mutinies, to WWII sabotage operations. Down to their core, each is a story of ordinary people set in extraordinary situations—and following how they achieve what may have seemed impossible. THE WICKED AND THE DEAD, and especially the beating heart of its narrative, James McParlan, fits perfectly within this wheelhouse.

Often during speeches, I explain how I go about choosing my subjects and what, if any, rules I follow. Two decades ago, I came up with two simple questions to answer. Here I've done the same.

1. Do I have something new to tell in this story? Immediately after these murderous events in 1870s coal country, a spate of books came out, some fantastically untrue, all sensationally told. In the 150 years since then, there have been periodic revisits, hewing to one ideologically bent or the other. The best, most recent title was a 1998 academic history called MAKING SENSE OF THE MOLLY MAGUIRES. There was even a biography published of McParlan’s long detective career, which included, in part, this tale, as well as a well-written rehash of his most significant cases in the West.

Humbly, none of these titles recount this history with much narrative momentum or cohesion. They are either sweeping compendiums of every violent act or hyper-focused on the Molly Maguires, as if they existed in a vacuum. In THE WICKED AND THE GOOD, I intend to inhabit each of the four main characters—McParlan, Gowen, Siney, and the Mollies—and how they were all pitted against each other. Under the theory that we are all heroes of our own stories, I will relate each from their own perspective, bringing all to vivid life

Already I have uncovered new research on each of these characters, and there are many archives still to plumb, including those of Gowen’s Reading Company, McParlan’s Pinkertons, and Siney’s union. All will be brought to bear in reshaping this narrative.

So, the answer to this question is an unequivocal yes.

2. Does this story have something important to say? I’ll keep this answer much more brief: YES. Of my shelf of books, few have offered such a richness of themes that were as relevant in the past as they are today. THE WICKED AND THE GOOD is a story of the age-old battle between capital vs. labor. It is a story about whether the ends justify the means. It is a story about power, immigration, law & order, and justice. As I say at the beginning of my proposal—and often throughout—this is a story about America.

Finally, this history sits very close to home. At night, from the rooftop of my Philadelphia townhouse, I can hear the whistle of trains coming down the same tracks that once brought heaps of 'black gold' into the city. I often hike about the same mountains to the north where miners once dug for coal. I know well the old coal towns of Pottsville, Shamokin, and Tamaqua. Here was once the beating heart of American industry, and if you ask the right people, you can still hear tales that have come down over the generations. This history remains alive in the hills and valleys of Pennsylvania. Better still, only a short walk in the city or a drive into the countryside, there are numerous collections of archives, some found in grand libraries, others in small local history museums, that reveal the truth of these events.

Okay. One bit of extra context. A final finally, promise: I'm a lover of true crime. From rereading Capote’s IN COLD BLOOD to binging WACO or DAHMER to rerunning films like Spike Lee’s BLACKkKLANSMAN to running while listening to SERIAL or my latest favorite, DR. DEATH. The high stakes, outsized emotions, ingenious puzzle-solving, and the "who," "what," "why," "when," and " where" of it all gets me every time. And besides my fandom, true crime works, often spectacularly well, in narrative non-fiction, especially historical stories. DEVIL IN THE WHITE CITY—true crime through and through. THE SUSPICIONS OF MR. WHICHER or MIDNIGHT IN THE GARDEN OF GOOD AND EVIL—true crime. Most recently, THE WAGER by David Grann is less a historical naval thriller than true crime drama from multiple angles. Sound familiar?

In any respect, I’ll leave it there. I'm thrilled to dive into this history and look forward to your thoughts!

Kindly yours,

Neal

THE WICKED AND THE GOOD

by Neal Bascomb

"What is the chief end of man? – to get rich. In what way? – dishonestly if we can; honestly if we must." –Mark Twain.

This is a quintessentially American story. Business titans. Company towns. A knight errant. Street justice. Murder. Greed. Mayhem. Corruption. Undercover agents. Class warfare. And the struggle to own your destiny.

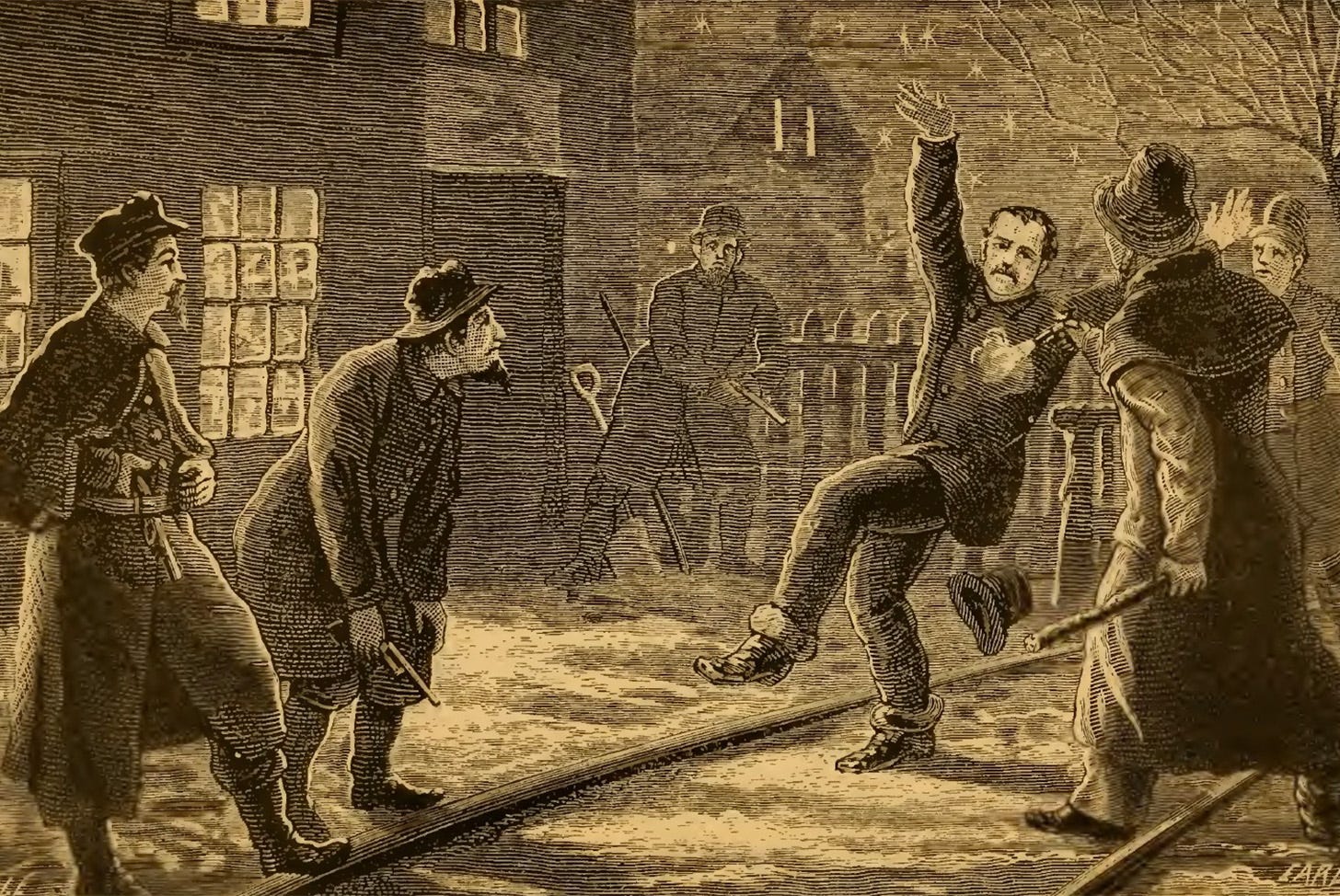

At the heart of the narrative is 28-year-old Irish immigrant James McParlan. He was a Chicago beat cop, now a rookie undercover detective, sent in as an itinerant worker and practiced counterfeiter to infiltrate a secret society responsible for a wave of terrible crimes. He has to insinuate himself into their ranks and win their trust. Once he gains membership, he must root out their leadership, gather evidence, and stop their destruction and killings. All the while, McParlan risks exposure at every turn and a swirl of competing pressures to end the violence. The toll of deceit and danger almost breaks him, and, in the end, he narrowly escapes an assassination attempt before testifying against those who would have had him dead.

The plot conjures a modern-day spin on FBI legends and movies like Donnie Brasco and The Departed, but McParlan went undercover 150 years ago. His target was the Molly Maguires, an Irish crime organization whose members were called everything from "lawless scum" to “heroes of the people” to "diabolical terrorists." As the New York Herald editorialized, "For the Molly Maguires, murder was but child's play, arson but a pleasure, and wickedness of all kinds but the natural outpourings of vile and devilish hearts." Although their exploits have largely been forgotten, they’re still whispered about in the lands in which they unfolded, an echo into our modern times of the eternal rift between the haves and have-nots.

The story opens at the dawn of the Gilded Age. The country had torn itself apart during the Civil War, and now its people bent their prodigious energy to making a buck. The divide between rich and poor had never been wider. The Carnegies and Vanderbilts of the country built extravagant marble palaces and threw even more extravagant parties. Immigrants teemed in filthy cities, cramming into tenements and laboring day and night in factories or breaking their backs mining coal or laying railroad tracks to propel the country into this new industrial age.

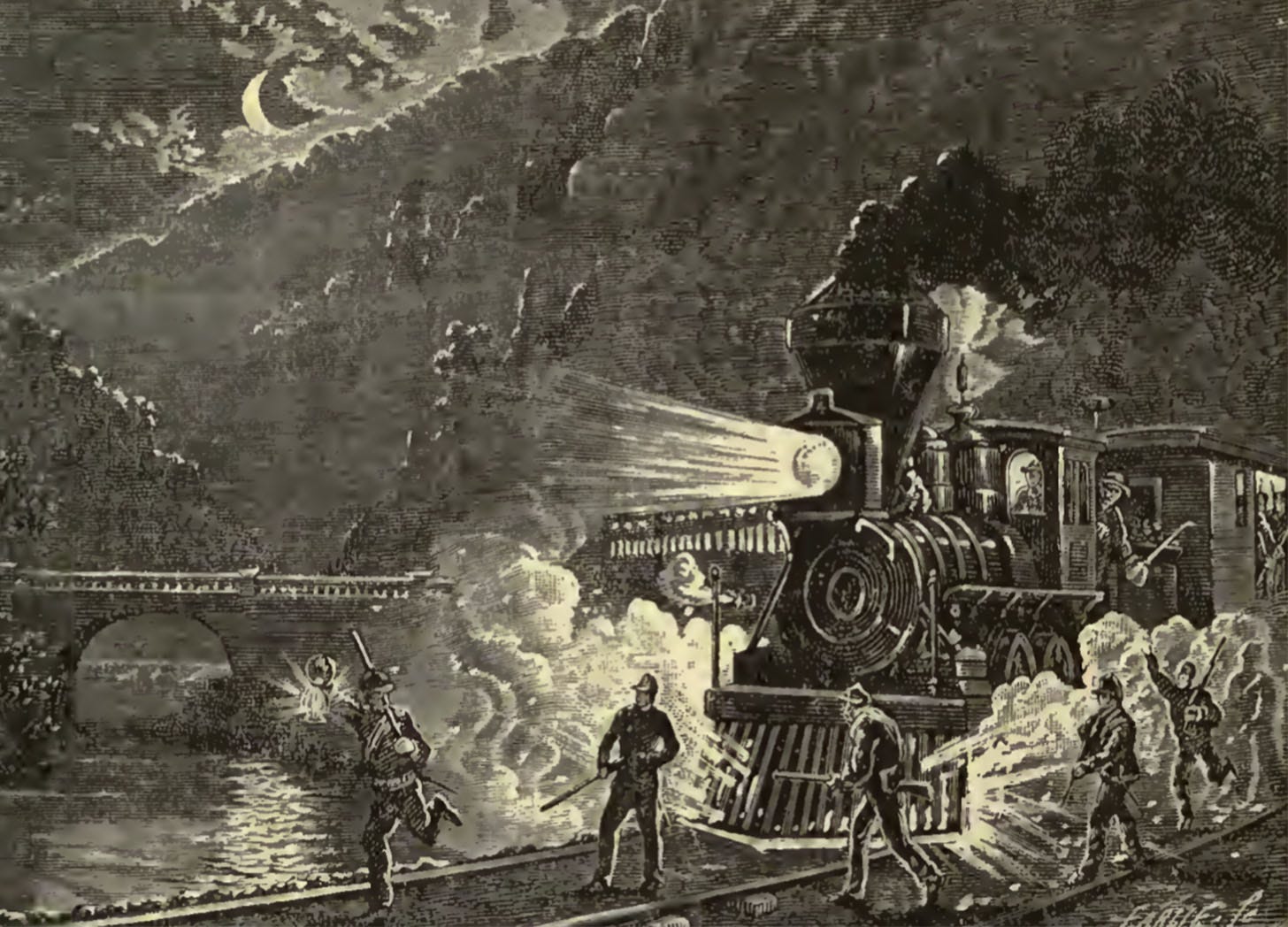

While historians have written much about reconstruction and the westward push after the Civil War, the most vital and awesome center of power in America during this period sat amidst the low mountains of Pennsylvania, equidistant between the citadels of New York City and Philadelphia. The area was the heart of anthracite coal, the "Black Gold" that fueled America's rise as a giant on the world stage. Sheared off the underbelly of the mountains and shipped by train in heaping piles, this dark hard rock with a metallic luster was made of almost pure carbon. It burned hot and nearly smokeless, providing cheap and efficient energy.

Everybody wanted and needed anthracite coal. It powered the steel forges of Pittsburgh and the textile mills of Boston. Homes, farmers, bakers, brewers, and small manufacturers all used coal. Steamboats plying the Mississippi from St. Louis to New Orleans fed their engines with it. Black gold made possible the railroads that connected the vast expanse of the United States, north to south, Atlantic to Pacific. Soon enough, it would provide the energy to electrify cities.

Whole industries emerged from the fountainhead of anthracite coal, so too vast fortunes. The economic boom it provided turned New York into a financial juggernaut where “Old World capital met New World ambition.” Black gold touched every part of American life, spinning a dynamic, often unrestrained flywheel of commerce. The insatiable appetite for more, ever more, of this rock swelled the greed of the titans of Pennsylvania coal and imposed unbearable demands on the miners who gave start to it all.

They lived in company-owned places called patches. They were more bustling land-locked ports than towns. They had a single purpose: retrieving anthracite coal from deep shafts and piling it into open train wagons to be hauled away for sale. Amidst northeastern Pennsylvania's long misty valleys and high blue-green hills, these patches looked like smoldering scars in an otherwise fair landscape. Single-track railroads connected one to the next. "It was not a cheering prospect," Arthur Conan Doyle wrote of a journey on such a line in The Valley of Fear, his fourth and final Sherlock Holmes novel, one inspired by these events. “Through the growing gloom, there pulsed the red glow of the furnaces on the sides of the hills. Great heaps of slag and dumps of cinders loomed up on each side, with the high shafts of the collieries towering above them. Huddled groups of mean, wooden houses, the windows of which were beginning to outline themselves in light, were scattered here and there along the line, and the frequent halting places were crowded with their swarthy inhabitants.”

Rough as these outposts appeared, choked with smoke and coal dust, they were also lively and filled with taverns, inns, gaming houses, clothiers, general stores, churches of several stripes, and concert halls. Patches had a modern, if gritty edge, that few such places in America could boast at the time for a population almost entirely made up of laborers. There was some stratification among the workers – the mining superintendents and bosses lived in the patches, too, but in well-built houses a comfortable distance from the shafts and churning colliers. A white picket fence usually surrounded their half-acre of land. But of course, as for the owners, many had never set foot in the patches, esconced in their townhouses in New York or Philadelphia or as far away as London.

Nevertheless, their money and power were always present in coal country, as was the reality of the unevenness of where it fell. For the well-to-do, who lived, in a sense, on the surface of this age's industry-and-tech hubs, the clangs of the mines and sooty air were physical manifestations of passive income, compounding interest, and advantage. They could hear and see themselves getting richer. For those whose labors generated that wealth, those who worked mainly below the ground, their lives were a Dantean hell.

Fortune on this scale – who got it and who didn't – would always be a problem. And a secret society known as the Molly Maguires would soon enough make it something that no one in the universe of black gold could ignore.

The war between the Molly Maguires and the barons of industry would cut to the quick of what America stood for and against.

Here are the plain facts…

[That should give you a good taste of the proposal. Paid subscribers can read the whole pitch. Hope you consider supporting in that way—and many thanks to those who already have!]

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Work/Craft/Life to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.