Path Lit by Lightning

Jim Thorpe and the 7 Unsung Qualities of the World’s Greatest Athlete

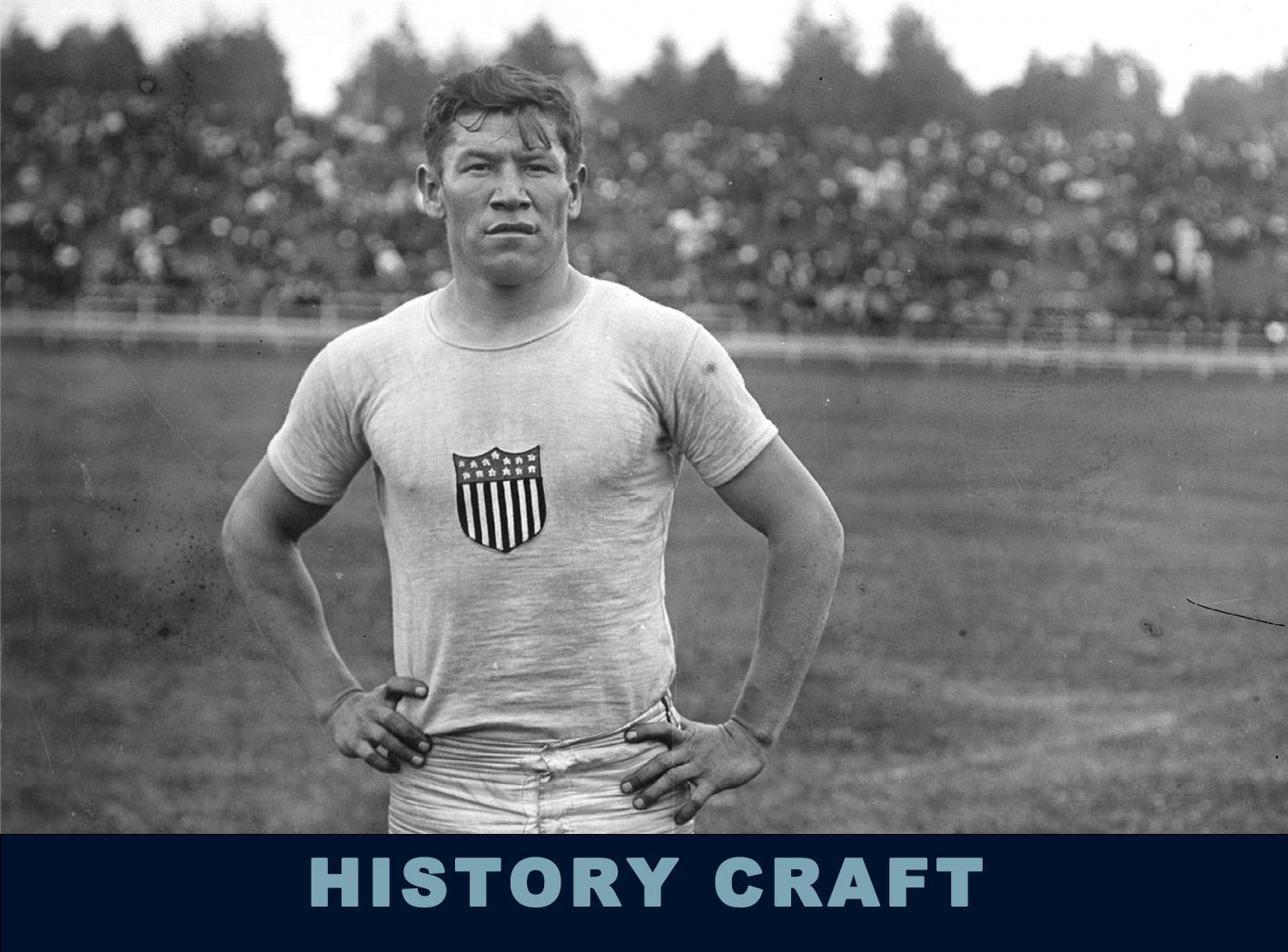

First off readers, some of you might have been expecting a profile of a zookeeper. That’s understandable since I promised one was coming. Alas, there was a hiccup during fact-checking, but it’s coming next Saturday. Instead, as evidenced by the photo above, I have some wonderful HistoryCraft.

In grade school, I read a short biography of Jim Thorpe, the Native American athlete who won two Olympic gold medals in track & field, reigned supreme on the football field, and played major league baseball. It was a hero’s story, without grays. The degradation of his Sac and Fox tribe and the forced assimilation Thorpe suffered at federally-run boarding schools like Carlisle and Haskell were barely noted. Further, his sporting prowess was tied almost exclusively to his early youth and natural abilities. As I recall, there were even illustrations of Thorpe running through the woods, hunting with a bow & arrow. The racist implications of this were only later clear.

A couple of months ago I read that David Maraniss, a two-time Pulitzer-Prize-winning journalist, had turned his many skills to the life of Thorpe. I bought Path Lit by Lightning straightaway. Like David’s biographies of Vince Lombardi, Roberto Clemente, and Barack Obama, this one did not disappoint. His portrait of Thorpe is incredibly well-researched, richly told, and clarifying on so many levels. Somehow it busts the myths that have long surrounded Thorpe and yet made him greater than I had ever imagined.

I was particularly captivated by how Maraniss identified the qualities Thorpe embodied that made him arguably the world’s greatest athlete of all time. Sure, he had natural-born talents, but there was so much more that elevated him into the pantheon of sport. Earlier this week, David and I had a conversation about his biography and Thorpe.

To set the context, what do you consider Thorpe’s finest athletic accomplishments?

Take one year: 1912. There are always arguments in sports, but in my opinion, this was the greatest single year of any athlete ever. First, he wins gold medals in the pentathlon and decathlon at the Stockholm Olympics, competing in 15 events in less than two weeks and just trouncing the field. He dominated those Olympics in a way that no one has since.

Then he comes back to America and plays football for the Carlisle Indian Industrial School in the fall of 1912. He was an All-American left halfback, defensive back, punter, and placekicker. He played entire games, did everything on the field, and dominated. The highlight of that year was November 9, 1912, when Carlisle played West Point. Indians against Army. And the Indians won 27-6. Thorpe was the star athlete in that game, and it rose him to the mythological level. 1912 epitomized his all-around talents.

He also played baseball in the major leagues. He could literally do almost anything. He was a basketball player and a great ballroom dancer. His buddies would say he was even great at marbles, whatever that entails.

Beyond natural physical abilities, what were the qualities—or workcraft—that made Thorpe such an extraordinary athlete? [This list of seven evolved out of our interview, and like the rest, is condensed and edited here in David’s words]

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Work/Craft/Life to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.