Juneteenth and 21st Century Slavery, a personal essay

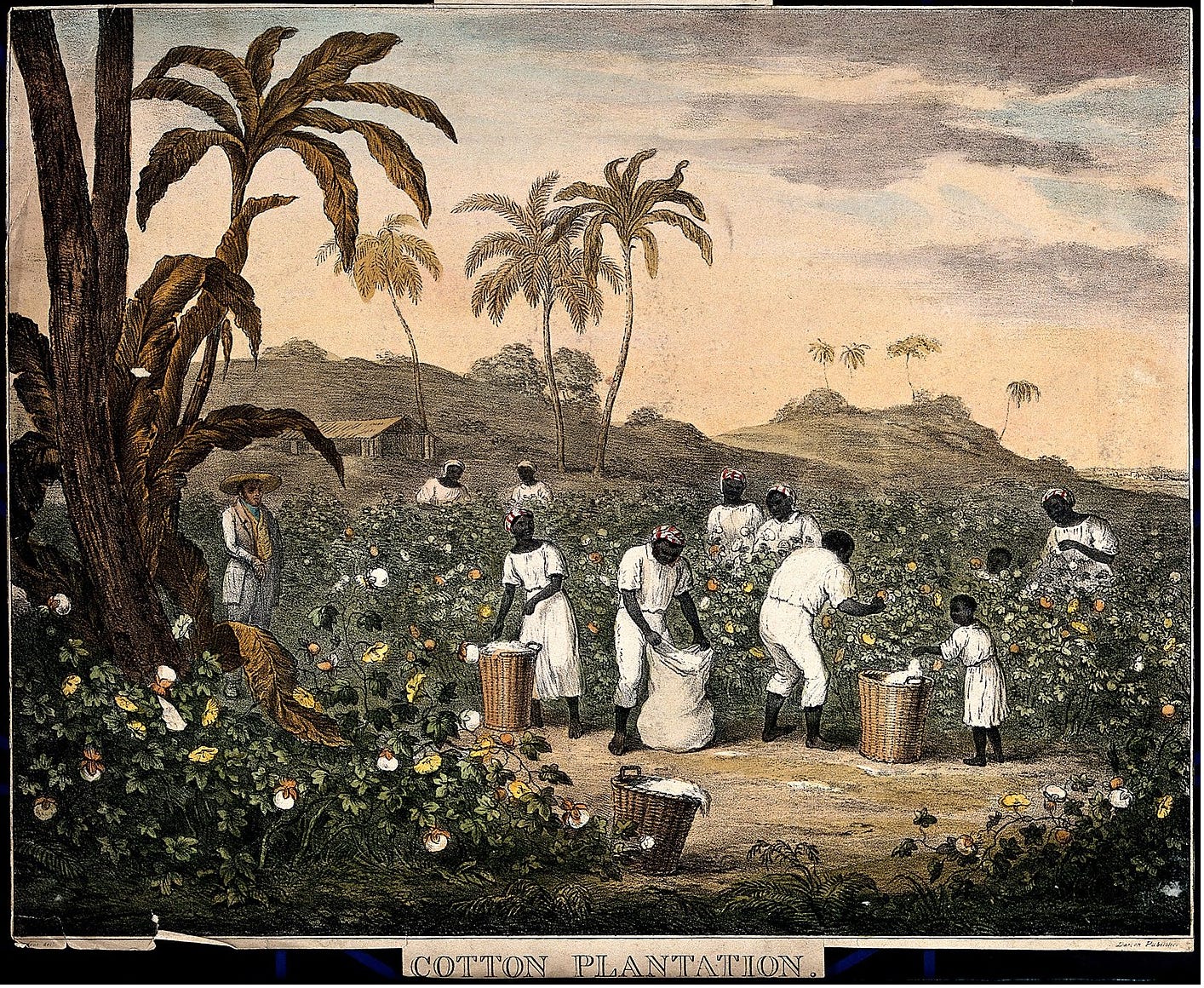

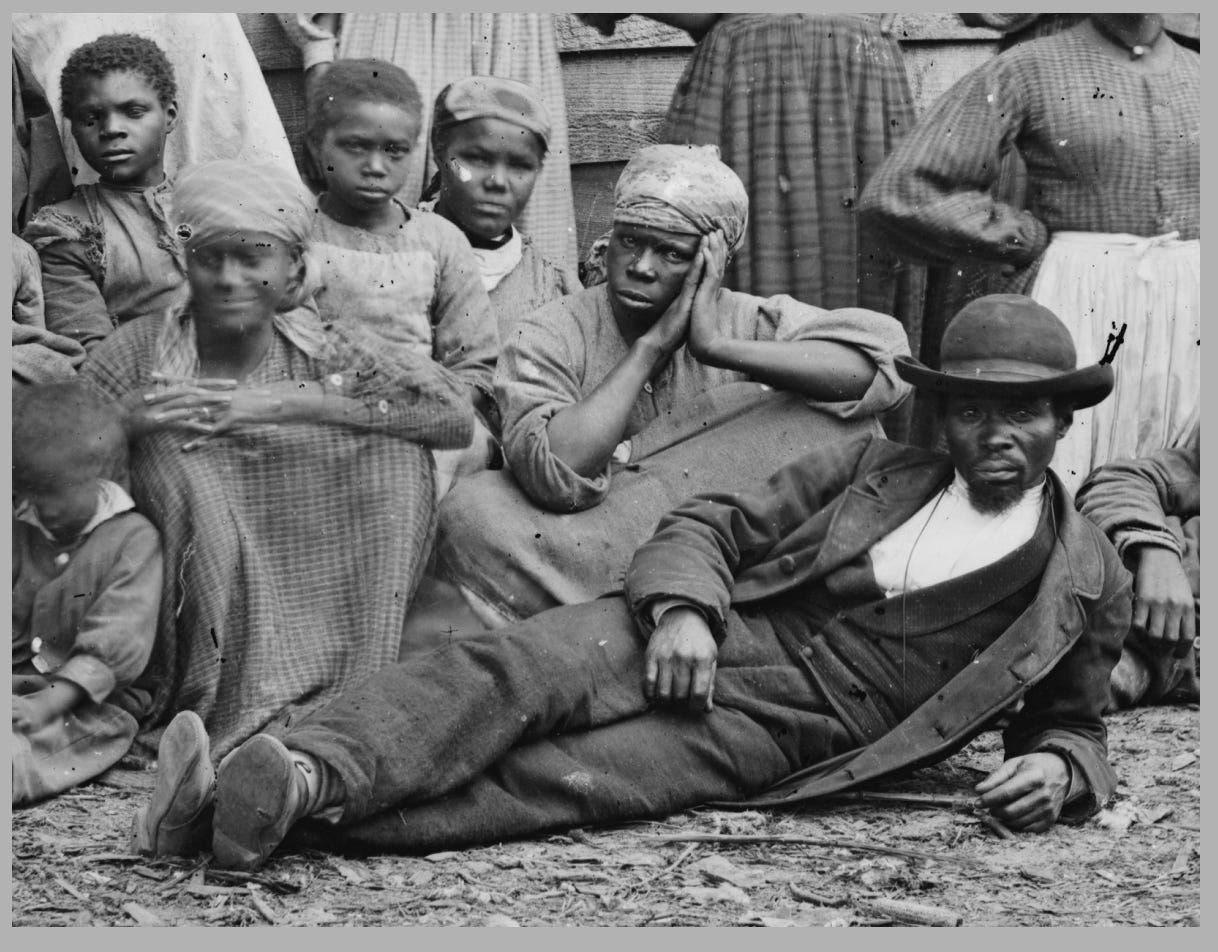

"From day-dawn till dark, under the constant eye of a master, the same dreary, monotonous, unchanging toil..."

Juneteenth, the annual commemoration of the effective end of slavery in the United States, is fast approaching this weekend. It is now a federal holiday, and amidst parties for Father’s Day on the 19th, one should take more than a moment to reflect on this important date.

In June 1865, Major General Gordon Granger arrived in Galveston, Texas with 2,000 federal soldiers. Throughout the city, he had General Order, No. 3 read out to its citizens: “The people of Texas are informed that in accordance with a proclamation from the Executive of the United States, all slaves are free. This involves an absolute equality of personal rights and rights of property between former masters and slaves, and the connection heretofore existing between them becomes that between employer and hired labor. The freedmen are advised to remain quietly at their present homes and work for wages.”

No doubt, this was only a beginning, signifying step toward the freedom—and equality—of black Americans in the United States. The struggle continues today, step by faltering step, and there are better, more apt modern writers to illuminate all that this means.

Since this newsletter aims to profile people and their work, I thought it a worthy endeavor to look back at slave narratives, and the descriptions of labor forced by the lash. Here are excerpts from three well-known narratives, one not. Thanks to the Works Progress Administration sending out interviewers from 1936-38 to speak with former slaves, we have over 2,300 individual recollections (available here from the Library of Congress) of this time. It is remarkable how similar they are to the below—and evidence of how systemized slavery had become in America.

1. Life & Times of Frederick Douglass, written by himself.

“Old and young, male and female, married and single, dropped down upon the common clay floor, each covering up with his or her blanket, their only protection from cold or exposure. The night, however, was shortened at both ends. The slaves worked often as long as they could see, and were late in cooking and mending for the coming day, and at the first gray streak of the morning they were summoned to the field by the overseer's horn. They were whipped for over-sleeping more than for any other fault. Neither age nor sex found any favor. The overseer stood at the quarter door, armed with stick and whip, ready to deal heavy blows upon any who might be a little behind time. When the horn was blown there was a rush for the door, for the hindermost one was sure to get a blow from the overseer. Young mothers who worked in the field were allowed an hour about ten o'clock in the morning to go home to nurse their children . This was when they were not required to take them to the field with them, and leave them upon “turning row " or in the corner of the fences. As a general rule the slaves did not come to their quarters to take their meals, but took their ashcake (called thus because baked in the ashes) and piece of pork, or their salt herrings, where they were at work.”

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Work/Craft/Life to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.